Hey! If you do front end development, you should know about CatchJS. It’s a JavaScript error logging service that doesn’t suck.

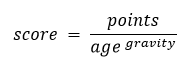

Below is a graph over the amount of searches for AngularJS versus a bunch of other Single Page Application frameworks. Despite the flawed methodology, the story seems to be pretty clear: Popularity wise, Angular is beating the shit out of the other frameworks. I spent most of last year working on a large project built on AngularJS, and I’ve gotten to know the framework in some depth. Through this work I have learned that Angular is built around some really bad ideas that make it a pain to work with, and that we need to come up with something better. Whatever the reason is for Angulars popularity, it isn’t that it’s a great framework.

The amount of searches for various SPA frameworks. (A less charitable interpretation of this data would be that Angular users have to search for answers more often than the others do.)

Bad Idea #1: Dynamic scoping

The scope of a variable is the part of the program where the variable can be legally referenced. If your system has variables, it has some concept of scoping.

Angular has a DSL that is entangled with the HTML and used primarily to express the data-bindings between the UI and application code. This has variables, and thus a concept of scopes. Let’s take a look at it. Consider for example ng-model:

|

1

|

<input type="text" ng-model="obj.prop" />

|

This creates a two way binding on the property prop of object obj. If you type into the input field, the property prop updates. If you assign to the property prop, the input field updates. Neat.

Now let’s add some simple parts:

|

1

2

3

4

|

<input type="text" ng-model="obj.prop" />

<div ng-if="true">

<input type="text" ng-model="obj.prop" />

</div>

|

Question: What does obj.prop refer to in the second input tag? The answer is that it is literally impossible to tell what meaning of ng-model=”obj.prop” is by reading the code. Whether or not the two “obj.prop” names refer to the same thing depends on the runtime state of the program. Try it out here: http://jsfiddle.net/1op3L9yo/ If you type into the first input field first, the two inputs will share the same model. If you type into the second one first, they will have distinct models.

WTF?

What’s going on here? Understanding that requires some knowledge of AngularJS terminology – skip this paragraph if you don’t care. The part that says ng-if is what’s called a directive. It introduces a new scope that is accessible as an object within the program. Let’s call it innerScope. Let’s call the scope of the first input outerScope. Typing “t” into the first input will automatically assign an object to outerScope.obj, and assign the string you typed to the property like so: outerScope.obj.prop = "t". Typing into the second input will do the same to the innerScope. The complication is that innerScope prototypically inherits from outerScope, so whether or not innerScope inherits the property obj depends on whether or not it is initialized in outerScope, and thus ultimately depends on the order in which the user interacts with the page.

This is insane. It should be an uncontroversial statement that one should be able to understand what a program does by reading its source code. This is not possible with the Angular DSL, because as shown above a variable binding may depend on the order in which a user interacts with a web page. What’s even more insane is that it is not even consistent: Whether or not a new scope is introduced by a directive is up to its implementer. And if a new scope is introduced, it is up to its implementer to decide if it inherits from its parent scope or not. In total there are three ways a directive may change the meaning of the code and markup that uses it, and there’s no way to tell which is in play without reading the directive’s source code. This makes the code-markup mix so spectacularly unreadable that one would think it is deliberately designed for obfuscation.

When variable scope is determined by the program text it is called lexical scoping. When scope is dependent on program state it is called dynamic scoping. Programming language researchers seem to have figured out pretty early that dynamic scoping was a bad idea, as hardly any language uses it by default. Emacs Lisp does, but that is only because Richard Stallman saw it as a necessary evil to get his Lisp interpreter fast enough back in the early 80s.

JavaScript allows for optional dynamic scoping with the with statement. This is dangerous enough to make Douglas Crockford write books telling you not to use it, and it is very rarely seen in practice. Nevertheless, with-statements are similar to how scoping works in Angular.

Pit of Despair

At this point, I imagine some readers are eager to tell me how to avoid the above problem. Indeed, when you know about the problem, you can avoid it. The problem is that a new Angular user likely does not know about the problem, and the default, easiest thing to do leads to problems.

The idea of the Pit of Success is said to have been a guiding principle in designing platforms at Microsoft.

The Pit of Success: in stark contrast to a summit, a peak, or a journey across a desert to find victory through many trials and surprises, we want our customers to simply fall into winning practices by using our platform and frameworks. To the extent that we make it easy to get into trouble we fail.

–Rico Mariani, MS Research MindSwap Oct 2003.

Angular tends to not make you fall into the Pit of Success, but rather into the Pit of Despair – the obvious thing to do leads to trouble.

Bad Idea #2: Parameter name based dependency injection

Angular has a built in dependency injector that will pass appropriate objects to your function based on the names of its parameters:

function MyController($scope, $window) {

// ...

}

Here, the names of the parameters $scope and $window will be matched against a list of known names, and corresponding objects get instantiated and passed to the function. Angular gets the parameter names by calling toString() on the function, and then parsing the function definition.

The problem with this, of course, is that it stops working the moment you minify your code. Since you care about user experience you will be minifying your code, thus using this DI mechanism will break your app. In fact, a common development methodology is to use unminified code in development to ease debugging, and then to minify the code when pushing to production or staging. In that case, this problem won’t rear its ugly head until you’re at the point where it hurts the most.

Even when you’ve banned the use of this DI mechanism in your project, it can continue to screw you over, because there are third party apps that rely on it. That isn’t an imaginary risk, I’ve experienced it firsthand.

Since this dependency injection mechanism doesn’t actually work in the general case, Angular also provides a mechanism that does. To be sure, it provides two. You can either pass along an array like so:

module.controller('MyController', ['$scope', '$window', MyController]);

Or you can set the $inject property on your constructor:

MyController.$inject = ['$scope', '$window'];

It’s unclear to me why it is a good idea to have two ways of doing this, and which will win in case you do both. See the section on unnecessary complexity.

To summarize, there are three ways to specify dependencies, one of which doesn’t work in the general case. At the time of writing, the Angular guide to dependency injection starts by introducing the one alternative that doesn’t work. It is also used in the examples on the Angular front page. You will not fall into the Pit of Success when you are actively guided into the Pit of Despair.

At this point, I am obligated to mention ng-min and ng-annotate. These are source code post-processors that intend to rewrite your code so that it uses the DI mechanisms that are compatible with minification. In case you don’t think it is insane to add a framework specific post-processor to your build process, consider this: Statically determining which function definitions will be given to the dependency injector is just as hard as solving the Halting Problem. These tools don’t work in the general case, and Alan Turing proved it in 1936.

Bad Idea #3: The digest loop

Angular supports two-way databinding, and this is how it does it: It scans through everything that has such a binding, and sees if it has changed by comparing its value to a stored copy of its value. If a change is found, it triggers the code listening for such a change. It then scans through everything looking for changes again. This keeps going until no more changes are detected.

The problem with this is that it is tremendously expensive. Changing anything in the application becomes an operation that triggers hundreds or thousands of functions looking for changes. This is a fundamental part of what Angular is, and it puts a hard limit on the size of the UI you can build in Angular while remaining performant.

A rule of thumb established by the Angular community is that one should keep the number of such data bindings under 2000. The number of bindings is actually not the whole story: Since each scan through the object graph might trigger new scans, the total cost of any change actually depends on the dependency graph of the application.

It’s not hard to end up with more than 2000 bindings. We had a page listing 30 things, with a “Load More” button below. Clicking the button would load 30 more items into the list. Because the UI for each item was somewhat involved, and because there was more to this page than just this list, this page had more than 2000 bindings before the “Load More” button was even clicked. Clicking it would add about a 1000 more bindings. The page was noticeably choppy on a beefy desktop machine. On mobiles the performance was dreadful.

Keep in mind that all this work is done in order to provide two-way bindings. It comes in addition to any real work your application may be doing, and in addition to any work the browser might be doing to reflow and redraw the page.

To avoid this problem, you have to avoid this data binding. There are ways to make bindings happen only once, and with Angular version 1.3 these are included by default. It nevertheless requires ditching what is perhaps the most fundamental abstraction in Angular.

If you want to count the number of bindings in your app, you can do so by pasting the following into your console (requires underscore.js). The number may surprise you.

function getScopes(root) {

var scopes = [];

function traverse(scope) {

scopes.push(scope);

if (scope.$$nextSibling)

traverse(scope.$$nextSibling);

if (scope.$$childHead)

traverse(scope.$$childHead);

}

traverse(root);

return scopes;

}

var rootScope = angular.element(document.querySelectorAll("[ng-app]")).scope();

var scopes = getScopes(rootScope);

var watcherLists = scopes.map(function(s) { return s.$$watchers; });

_.uniq(_.flatten(watcherLists)).length;

Bad Idea #4: Redefining well-established terminology

A common critique is that Angular is hard to learn. This is partly because of unnecessary complexity in the framework, and partly because it is described in a language where words do not have their usual meanings.

“Constructor functions”

In JavaScript, a constructor function is any function called with new, thus instantiating a new object. This is standard OO-terminology, and it is explicitly in the JavaScript specification. But in the Angular documentation “constructor function” means something else. This is what the page on Controllers used to say:

Angular applies (in the sense of JavaScript’s `Function#apply`) the controller constructor function to a new Angular scope object, which sets up an initial scope state. This means that Angular never creates instances of the controller type (by invoking the `new` operator on the controller constructor). Constructors are always applied to an existing scope object.

https://github.com/angular/angular.js/blob/…

That’s right, these constructors never create new instances. They are “applied” to a scope object (which is new according to the first sentence, and existing according to the last sentence).

“Execution contexts”

This is a quote from the documentation on scopes:

Angular modifies the normal JavaScript flow by providing its own event processing loop. This splits the JavaScript into classical and Angular execution context.

https://docs.angularjs.org/guide/scope

In the JavaScript specification, and in programming languages in general, the execution context is well defined as the symbols reachable from a given point in the code. It’s what variables are in scope. Angular does not have its own execution context any more than every JavaScript function does. Also, Angular does not “modify the normal JavaScript flow”. The program flow in Angular definitely follows the same rules as any other JavaScript.

“Syntactic sugar”

This is a quote from the documentation on providers:

[…] the Provider recipe is the core recipe type and all the other recipe types are just syntactic sugar on top of it. […] The Provider recipe is syntactically defined as a custom type that implements a $get method.

https://docs.angularjs.org/guide/providers

If AngularJS was able to apply syntactic sugar, or any kind of syntax modification to JavaScript, it would imply that they had their own parser for their own programming language. They don’t*, the word they are looking for here is interface. What they’re trying to say is this: “Provide an object with a $get method.”

(*The Angular team does actually seriously intend to create their own compile-to-JS programming language to be used with Angular 2.0.)

Bad idea #5: Unnecessary complexity

Let’s look at Angular’s dependency injector again. A dependency injector allows you to ask for objects by name, and receive instances in return. It also needs some way to define new dependencies, i.e. assign objects to names. Here’s my proposal for an API that allows for this:

injector.register(name, factoryFn);

Where name is a string, and factoryFn is a function that returns the value to assign to the name. This allows for lazy initialization, and is fully flexible w.r.t. how the object is created.

The API above can be explained in two sentences. Angular’s equivalent API needs more than 2000 words to be explained. It introduces several new concepts, among which are: Providers, services, factories, values and constants. Each of these 5 concepts correspond to slightly different ways of assigning a name to a value. Each have their own distinct APIs. And they are all completely unnecessary, as they can be replaced with a single method as shown above.

If that’s not enough, all of these concepts are described by the umbrella term “services”. That’s right, as if “service” wasn’t meaningless enough on its own, there’s a type of service called a service. The Angular team seem to find this hilarious, rather than atrocious:

Note: Yes, we have called one of our service recipes ‘Service’. We regret this and know that we’ll be somehow punished for our misdeed. It’s like we named one of our offspring ‘Child’. Boy, that would mess with the teachers.

https://docs.angularjs.org/guide/providers

Einstein supposedly strived to make things as simple as possible, but no simpler. Angular seems to strive to make things as complicated as possible. In fact it is hard to see how to complicate the idea of assigning a name to a value any more than what Angular has done.

In conclusion

There are deep problems with Angular as it exists today. Yet it is very popular. This is an indication of a problem with how we developers choose frameworks. On the one hand, it’s really hard to evaluate such a project without spending a long time using it. On the other hand, many people like to recommend projects they haven’t used in any depth, because the idea of knowing what the next big thing is feels good. The result is that people choose frameworks largely based on advice from people who don’t know what they’re talking about.

I’m currently hoping Meteor, React or Rivets may help me solve problems. But I don’t know them in any depth, and until I do I’ll keep my mouth shut about whether or not they’re any good.

. Libscore gives good numbers for the denominator. Turns out there are at least a couple of ways to get useful numbers for the numerator as well.

. Libscore gives good numbers for the denominator. Turns out there are at least a couple of ways to get useful numbers for the numerator as well.